“When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood!

“Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign (flag) of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full and high advanced... not a strip erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured, bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as “What is all this worth?” nor those other words of delusion and folly, “Liberty first and Union afterwards”; but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart – Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

–Senator Daniel Webster in the Senate, second speech on Foote’s resolution, January 26, 1830

“Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign (flag) of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full and high advanced... not a strip erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured, bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as “What is all this worth?” nor those other words of delusion and folly, “Liberty first and Union afterwards”; but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart – Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

–Senator Daniel Webster in the Senate, second speech on Foote’s resolution, January 26, 1830

Indeed, let us remember history. However, in the case of the American Civil War, let us consider not just the romanticized, sympathetic views of the Lost Cause and the Confederacy. We must possess the wisdom to separate fact from fiction to determine what or what not should be revered; why or why not it should be honored; and where or where not war memorials should be displayed.

The quote above is part of a speech made in 1830 by Daniel Webster in the United States Senate. Of course, Webster spoke these words long before the South succeeded from the Union. Now, they serve as a lantern to illuminate some of the darkest hours of American history.

The speech is widely considered the most famous senate speech in history. And, for good reason.

South Carolina Senator Robert Hayne entered the debate as a surrogate for Vice President John C. Calhoun. Hayne agreed that land sales should be ended. In his opinion, they enriched the federal treasury for the benefit of the North, while draining wealth from the West. At the heart of his argument, Hayne asserted that states should have the power to control their own lands and – to disobey or "nullify" federal laws that they believed were not in their best interests. Hayne continued that the North was intentionally trying to destroy the South through a policy of high tariffs and its increasingly vocal opposition to slavery.

In a packed Senate chamber Daniel Webster rose to Haynes challenge. The gifted orator began a two-day speech known as his Second Reply to Hayne. In response to Hayne's argument that the nation was simply an association of sovereign states, from which individual states could withdraw at will, Webster thundered that it was instead a "popular government, erected by the people; those who administer it are responsible to the people; and itself capable of being amended and modified, just as the people may choose it should be."

The editor of Webster's papers wrote that until 1830, the United States was "a loosely-knit confederation of states, the division of power between them still unclear despite the valiant efforts of Chief Justice John Marshall. After January 27 the United States was a nation, no longer a plural but a singular noun." While many historians would contend that such a result was only achieved by the Civil War, Webster may have planted a seed that bore fruit later.

For millions of people in 1861, Webster's words were a driving motivation: Liberty (ending slavery), and Union (keeping the nation intact). Pursuing that double objective resulted in over 600,000 American lives being lost and an additional 410,000 maimed and crippled, making it by far the bloodiest war in American history.

Understanding

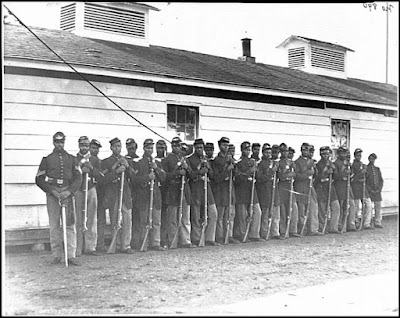

Union Service

Douglas said, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship."

Black Americans were not just spectators in the Civil War. They were active participants in battles and in running the Underground Railroad.

In addition, many blacks – including women – worked as nurses, cooks, laborers, and blacksmiths. Some were spies and scouts. And, this was not the beginning of their American service: they also fought in the Revolutionary War and in the War of 1812.

At first their service in the Civil War was denied. Federal law dating from 1792 barred Negroes from bearing arms for the U.S. army (although they had served in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812). By mid-1862, however, the escalating number of former slaves (contrabands), the declining number of white volunteers, and the increasingly pressing personnel needs of the Union Army pushed the Government into reconsidering the ban.

As a result, on July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had masters in the Confederate Army. Two days later, slavery was abolished in the territories of the United States, and on July 22 President Lincoln presented the preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet. After the Union Army turned back Lee's first invasion of the North at Antietam, MD, and the Emancipation Proclamation was subsequently announced, black recruitment was pursued in earnest. In fact, two of Douglass's own sons contributed to the war effort.

Many black soldiers became American heroes, displaying great courage and deep Christian faith. Sixteen black soldiers won the Congressional Medal of Honor for their brave service in the Civil War. Some scholars believe the infusion of black soldiers may have turned the tide of the war.

Black soldiers faced additional problems stemming from racial prejudice. Racial discrimination was prevalent even in the North, and discriminatory practices permeated the U.S. military. The treatment of most colored soldiers was sub-standard, and they often bore the brunt of ridicule and violence

Discrimination in pay and other areas remained widespread. According to the Militia Act of 1862, soldiers of African descent were to receive $10.00 a month, with an optional deduction for clothing at $3.00. In contrast, white privates received $13.00 per month plus a clothing allowance of $3.50.

Black soldiers and their officers were also in grave danger if they were captured in battle. Confederate President Jefferson Davis called the Emancipation Proclamation the most execrable measure in the history of guilty man” and promised that black prisoners of war would be enslaved or executed on the spot. (Their white commanders would likewise be punished—even executed—for what the Confederates called “inciting servile insurrection.”)

Despite the ever-present dangers, nearly one in ten soldiers in the Union Army were African American. The compiled military service records of the men who served with the United States Colored Troops (USCT) during the Civil War numbered approximately 185,000, including the officers who were not African American. And, there were nearly 80 black commissioned officers.

Blacks fought in 449 Civil War battles. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war – 30,000 of infection or disease.

Yet, soon, the American nation had all but forgotten that black troops had ever played a major role in the Civil War. The popular image of the Civil War was that it was “a white man's fight.” It is almost inconceivable that the black regiments’ service was long remembered as a small part of the Civil War, especially with the U.S. military remaining strictly segregated until 1948.

In the Grand Review of the Armed Forces which followed the end of hostilities very few blacks were represented. In these reviews, black veterans were relegated to the end of the procession in “pitch and shovel” brigades or intended only as a form of comic relief. Neither the free black soldier not the former slave was accorded his deserved role in this poignant national pageant.

The Civil War was fought for Union and Liberty. In his famous address of 1830, Daniel Webster defended the case for an enduring federal union, and he found slavery “one of the greatest evils, both moral and political.” The preservation of the Union during the Civil War led to the end of slavery. If it were not for the service and sacrifices of black Union troops, the Union may have fallen and slavery might have survived until who knows when.

Confederate monuments and statues symbolize both the institution of slavery and succession from the United States. How do we preserve these tributes and, at the same time, show proper respect for black America? The decision must reflect right, not concerns for the preservation of the culture of the Old South. We are bound to a commitment to do what is correct.

If such memorials remain, they should take their proper place in a setting that defines their dark roles as they relate to the history of liberty and union – those concepts forever “dear to every true American heart.”

"In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me:

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

"Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

His truth is marching on."

No comments:

Post a Comment